The Bakrwal Community In Pakistan

By Fatima Tuz Zahra

Introduction

An indigenous community in Pakistan; The BAKRWAL community belongs to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and regions of Azad Jammu, and Kashmir. The community is also situated in our neighboring country, India. They mainly reside in Indian-occupied Jammu Kashmir and Ladakh and have spread over a large area from Pir Panjal to Zanskar in the Himalayan Mountains of India. They belong to the Muslim faith and practice the Sunni School of thought. For centuries they have passed down a nomadic way of life with which they are deeply connected and rely on forests and pastures for their livelihoods.

Origins

The origins of the Bakarwal community have been a subject of ongoing scholarly debate. Various theories exist regarding their ancestry, with some claiming that they are a subgroup of the Gujar tribe. For instance, Cunningham (1871) posited that their lineage can be traced back to the Scythian tribe, which invaded Kabul around 100 BC and later settled in regions such as Kashmir, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Gujarat before establishing the Gujar kingdom. Additionally, some sources suggest a connection to the white Huns who arrived in India in 465 AD. On the other hand, some scholars argue that the Bakarwal community has roots solely in India. Nevertheless, a prevailing belief maintains that the Gujars are descended from the Georgians.[i]

Language

The Bakarwal people are mainly goat and sheep herders. “Bakar wal” means “high altitude Goatherds/Shepherds”. This nomadic community seasonally migrates from one pasture to another in search of grassland for their livestock. Gojri being the mother tongue of the tribal Bakarwal community as well as the Gujjar community, is spoken in slight variations among the two communities However it’s the most preferred and comfortable language to use.

Although both communities speak the same language, there are slight variations in the pronunciation, tone, mannerisms, and names of things, for example, the Bakarwals call children ‘Gadre’ whereas the Gujars refer to them as ‘Gadri’. The Bakarwal name for the wooden pillar is ‘Phaut’ however the Gujars call it ‘Khamba. Another example is the Bakarwals say ‘tu kit chalo’ when asking where are you going whereas the Gujars say’ tukiyaChalo’ when addressing the same question.[ii]

The resemblance of Gojri with Urdu and Mewari (Rajasthani) is hard to ignore that’s because all of these languages have a lot in common the main being that both the languages (Urdu and Gojri) belong to the family of Indo-Aryan languages.ii

The indigenous language of the Gujar and Bakarwal communities lacks its script and relies heavily on Arabic and Urdu forms of writing. Due to low literacy and limited availability of literature and books in their mother tongue, the people in these communities are completely unaware of the written form of their language.ii

Besides Gojri, the community people are multilingual and can understand and interact fluently in Kashmiri, Pahari, Pakhtoon, and Urdu. However, in intra-community interactions, their mother tongue is predominantly used but Urdu is mostly spoken in inter-community transactions and communications.ii

Despite being multilingual, there is no doubt that the mother tongue facilitates learning and enables people to understand concepts and phenomena more easily. The community’s preferred language is still their mother tongue, Gojri. They emphasize that all subjects should be taught in their mother tongue.ii

The Climate Crisis And Its Effects

The Bakarwal community is grappling with significant disruptions to their traditional lifestyle caused by extreme weather patterns including prolonged rain, snow, and heat. The harsh weather and unplanned changes, such as heavy rain, are posing significant challenges to their nomadic journeys, compelling them to forsake their age-old way of life. These difficulties are undeniably linked to the climate crisis.

According to the article published on Dialogue Earth by Shabina Faraz ‘Pakistan’s centuries-old Bakarwal community faces a dual threat’ where she mentions the effects of extreme heat on the community’s livelihood; “Rauf said the animals struggle in extreme heat, remembering a year when “we spent four months in the Deosai pastures, where the temperature is usually 6C to 8C. But when we reached the plains of Punjab at the end of October, the temperature was above 35C. Our animals could not bear this change in temperature. They fell ill and had to be sold. It was not like this before.” Due to extreme weather conditions, a lot of the sheep fall ill or die affecting the community in unimaginable ways. Climate change is now one of the biggest threats to the nomadic life of the Bakarwal community.[iii]

Administrative Restrictions

The Climate crisis is one, but many other developments are proving to be hurdles such as administrative restrictions for example, the forest department has banned the Bakarwals and many such tribal communities from traveling through the forests of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa due to Imran Khans ‘Billion tree Tsunami project’ the livestock is forbidden from traveling on foot to protect plants since Goats uproot plants. Because of this, they have no choice but to transport their animals by vehicle which comes with complications. A lot of the time the animals get injured due to the rocky terrain of the mountains or end up suffocating or even dying. The Bakarwals also believe that traveling on foot is good for animal health. Another complication is that many people from the community can’t afford to travel through vehicles. The Bakarwal community has protested against the forest department over these developments in recent years.iii

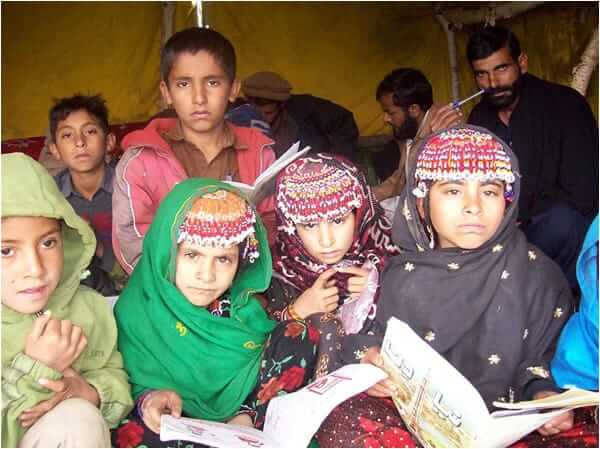

Education

Regarding literacy and education, Bakarwal and such nomadic communities are subject to marginalization making acquiring formal education difficult. Many education frameworks and curricula don’t cater to such people of diverse cultures, few educators speak in their dialect or language or understand or want to preserve their way of life.

“The Bakarwal people have lived a nomadic life for generations and find it to be an intrinsic aspect of their culture and identity. Due to rapid population growth, inflation, and increased restrictions to public grazing areas, they are finding this traditional way of life is under threat. At the same time, due to the structure and content of the current education system, Bakarwal nomads remain largely illiterate and at an economic disadvantage due to a lack of relevant educational opportunities” says Brandon Baughn, Director of BMS (Bakarwal Mobile Schools).[iv]

The Bakarwal nomads face a difficult decision when it comes to educating their children. In order to provide formal education, many families must give up their traditional nomadic lifestyle and either settle on the peripheries of towns or send their children to religious schools known as Madrassas. This shift away from their traditional ways not only leads to a loss of cultural and linguistic identity but also puts the unique Bakarwal culture at risk of vanishing altogether. This is concerning because the Bakarwal community plays a significant role in maintaining the balance of local ecosystems and contributing to the local economy.

BMS/THLN

However, BMS/THLN (Bakarwal Mobile Schools, The Himalayan Literacy Network) wants to make things better for these communities by preserving their culture while also achieving progress through education.

The primary goal of the Himalayan Literacy Network program is to establish mobile schools that can be relocated and set up for several months at a time, following the migratory patterns of the communities. This initiative aims to preserve their unique way of life and ensure that their traditional knowledge and practices are not lost. Their curriculum also allows them to start schooling in their mother tongue which is Gojri, keeping their identity intact and eventually progressing to Urdu and then English by the end of fifth grade. THLN helps equip the community members for an ever-changing world while also making sure they don’t lose themselves and their cultural identity and heritage in the process.[v]

Due To THLN’s efforts, over 3000 children and approximately 40 adults have received basic education since 2007 through this program.v

Tribal Education In India

In terms of literacy and tribal education, specifically in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir, which is home to numerous tribes such as the Bakarwals and the Gujjars, the 2011 census reported a total scheduled tribe population of 1,493,299 in the region.[vi]

The literacy rate of the tribal population of Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir is 50.6% as per the 2011 census.vi

The Gujjar and Bakarwal communities comprise 11.9% of the total population in Occupied Jammu and Kashmir, making them the largest ethnic group in the region. According to the 2001 census, the literacy rate among the Gujjars was 31.65%, and among the Bakarwals was 22.51%, totaling 55.52% of the general population in the occupied state.[vii] Over a span of 10 years (2001-2011), an increase in the literacy rate from 37.50% to 50.6% was observed, indicating tangible progress at the grassroots level. However, there is still room for improvement, as the literacy rate in Occupied Jammu and Kashmir remains lower than the national average for tribal populations, which stands at 58.96%. It’s worth noting that no new census data have been released since 2011 based on my research.vi

Conclusion

The Bakerwal way of life is deeply interconnected with the environment, and its loss would have far-reaching consequences for the community and the surrounding ecosystems. These indigenous communities play a critical role in maintaining ecological balance. For instance, the nomadic lifestyle of the Bakerwals and their herds is essential for fixing the nutrient cycle in the meadows by naturally providing nitrogen and phosphorus. Additionally, their animals are invaluable contributors to organic meat, wool, and leather industries and play a crucial role in pollination.

Unlike conventional farming practices, the Bakerwal community does not overgraze in one area and instead moves their herds based on the land’s carrying capacity. This sustainable approach ensures that resources are not overexploited. Their nomadic lifestyle significantly influences the environment and economy of the regions they inhabit. If this traditional way of life were to vanish, it would disrupt the delicate balance of the mountain ecosystem and lead to the loss of a sustainable and affordable livestock production system.

[i] https://www.arfjournals.com/image/catalog/Journals%20Papers/IJAR/2023/No%201%20(2023)/5_Upaid.pdf

[ii] https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED618113.pdf

[iii] https://dialogue.earth/en/nature/bakarwal-community-faces-dual-threat-pakistan/

[iv] https://dialogue.earth/en/nature/bakarwal-community-faces-dual-threat-pakistan/

[v] https://gujjarbakarwal.org/en/bakarwal-mobile-schools-pk

[vi] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298175898_MYTHS_AND_REALITIES_OF_TRIBAL_EDUCATION_IN_JAMMU_AND_KASHMIR_AN_EXPLORATORY_STUDY

[vii] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325883655_Socio-Economic_and_Educational_Status_of_Tribal_Gujjar_and_Bakarwal_of_Jammu_and_Kashmir_An_Overview

Fatima Tuz Zahra is a sociology student who has a genuine passion for understanding different cultured and recognizing the interconnectedness of societal issues. She’s particularly interested in how these dynamics uniquely manifest in Pakistan

1 Comment

Thank you for this article. I lived in Gujranwala and went to school in Murree during the 60s. I remember the Bakarwal people in Murree when I lived there. I was only a boy and was a bit intrigued but also a bit frightened of them. For some reason they have become a point of fascination with me in my later years. (Maybe because I have sheep and goats of my own.)

I was wondering if you could tell me of common names for the men and for the women? I am thinking of writing a little story for my grandkids.

Thank you so much!