Extremism on Campus

By Zeeba T. Hashmi

https://dailytimes.com.pk/

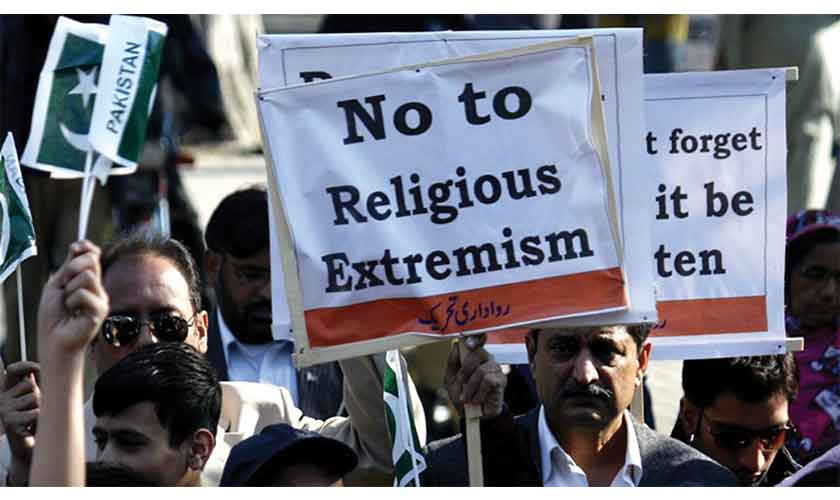

The news that was conveniently ignored by authorities is of girls getting attacked by the activists of the student group Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba (IJT) for playing cricket on the campus of Karachi University with their male counterparts near a bus stop. The Rangers, in response, arrested four IJT activists but released them only half an hour later. The IJT spokesman has rejected the claim that their activists harassed the women. And whilst the incident happened before scores of witnesses, no investigative action has been taken against the attackers. The resilient female students fought back, this time by playing cricket on the premises of the administration building of the varsity.

This, unfortunately, is not the first incident of its kind where an extremist student party like the IJT has been implicated for public harassment. On Independence Day the same year in 2015, activists of the IJT assaulted and injured some members and teachers of Punjab University’s administration when they objected to their holding a ceremony without informing them. They have been involved in physically threatening different faculty members and students time and again. In imposing authoritative religious codes on campus, right-wing student activists targeted both men and women for being ‘liberal’. They continue to intervene in academic debates that they fear are challenging their values. They force students in dormitories to participate in protests organised by their mother party, the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI). They react violently against those who protest their sheer vigilantism. The IJT formed a parallel administration on these campuses. The demands of the affected faculty members and students to take action against their terrorising tactics have all been futile. Their intimidation and violence against peers is no secret to anyone and the authorities are well aware of their activities in inciting trouble on campus. Their mobs are beyond anybody’s control. Even their mother political party, the JI, feels helpless about them. It is because of antics like these on campus that academic life was never able to flourish fully, as religion is always brought into discourse that is required to be unbiased and progressive.

Campus extremism is a subject that needs to be understood in political and historical terms. Social mobility for the sake of initiating revolution has great reliance on university students to take a stand. We have witnessed student activism in the 1960s and 1970s when there was strife against military dictatorships in the country defining the foreign policies of the state. To control the students’ political trends, for example, when the popular leftist student wings were in full swing, they were countered by enabling armed right-winged groups against them, which took advantage of their intra-party differences. The changing political scenario of Pakistan also affected student political trends and the IJT, as a right-wing student party, was encouraged as an authoritarian force on campuses across Pakistan in a bid to diminish ant-Zia sentiments in students.

The state’s inability to tackle extremism remained worrisome especially because Islamists on campus have alleged links with terrorist organisations — some al Qaeda operatives were also arrested from dormitory rooms under direct control of the IJT. Favourable conditions are present for their recruitment.

Why is it that we are witnessing university graduates participating and even masterminding acts of terrorism here? It would be extremely wrong to presume that our educational institutions are free from elements that are responsible for the inculcating of violent religious indoctrinations in students. Universities play a pivotal role in designing academic discourses and pave the way for scientific evolution. The process appears to be stagnated here, which provides for a breeding ground for propagation of a fundamentalist mindset in students.

It is the ideologies, not a social class of people, that cater to the determinants of recruitment by jihadist organisations. A case study of Faisal Shahzad breaks away from the theory that terrorism is mainly caused by sheer poverty, as we see the pattern in recruitment into militant madrassas (seminaries) in our tribal belts. It is the environment that allows for radicalisation to take place. It is true that the recruitment process by jihadis includes material provisions to poor families in return for sending their children to the madrassas but such children, unlike university jihadi recruits, may or may not be as ideologically driven as they are by the finances they or their families receive.

While it is to be tested by time the seriousness of our state to finally counter the extremism that has seeped into our social structure uncontested, there remains a crying need to address the underlying reasons to understand why our society’s mindset, on the whole, borders on extremist ideologies. To become concerned about the youth becoming more and more rigid and devoid of any rationality, we have to understand why free thought and political movements have remained limited and suppressed in history, allowing for designed monolithic discourse to fill in the intellectual void. This is not to say that our regional cultures have never been open before but they remained restricted mainly by their pre-defined traditions and social mores. Hence, in, contrast, the religious fundamentalism we see here is more prominent in urban areas or among the middle income class than in rural societies. It is noteworthy that extreme religious education is not just emanating from extremist elements but also from its supporters who are active in schools, modern institutes and universities in the name of religion. The fundamentalism that we see around us is perpetuating from electronic media and populist literature, which centres its wisdom on religious indoctrinations and abhors any such notion that refutes the premise of religion. This indeed has its historical roots that gradually made Pakistani society less tolerant. Religious preaching and recruitments in our educational institutions have, in fact, stolen our collective ability to think rationally. If the activities by right-wing student parties are not addressed before they get out of hand, the situation in our universities will become another fiasco similar to that of Lal Masjid.

Zeeba T. Hashmi is an opinion writer and a researcher exploring themes of education that interconnect with issues of indoctrination, hate speech, knowledge barriers and politics on education. She runs her think tank, Ibtidah for Education.