Macaulay’s Legacy and Today’s Pakistan

By Rab Nawaz

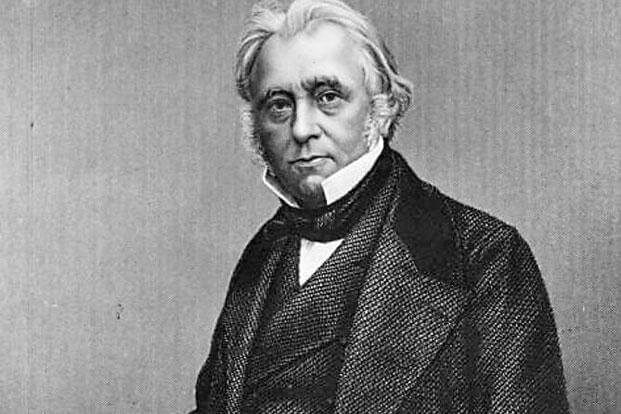

It’s been a decade less than two centuries since the British decided to colonize India through medium of education. The decision was brought about through English Education Act 1835 of which Lord Macaulay was the chief architect. According to the Act, English was made the medium of instruction with the aim of promoting Western culture and denigrating the local Indian traditions. Had this policy persisted only until the end of British Empire, it would have been merely a matter of the past. But the fact remains that this is still the broader approach that defines education system in Pakistan, at least part of the system which caters to the ruling class in Pakistan. This calls for a reexamination of Macaulay’s legacy and its relevance in today’s Pakistan.

Before going any further, a caveat on what Macaulay stood for. There is a famous passage going rounds which goes as follows:

“I have travelled across the length and breadth of India and I have not seen one person who is a beggar, who is a thief. Such wealth I have seen in this country, such high moral values, people of such calibre, that I do not think we would ever conquer this country, unless we break the very backbone of this nation, which is her spiritual and cultural heritage, and, therefore, I propose that we replace her old and ancient education system, her culture, for if the Indians think that all that is foreign and English is good and greater than their own, they will lose their self-esteem, their native self-culture and they will become what we want them, a truly dominated nation.”

This passage is falsely attributed to Lord Macaulay. Macaulay never said these words, however, it does not exonerate him of other racist comments he made. He has famously said in his February 02, 1835 speech in the British parliament, “a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia”. He said this on the occasion of the passing of English Education Act when the East India Company decided to drop funding for Hindi and Arabic and chose English in their place. He made similar remarks in the said speech which reflect his understanding of European civilization as superior to that of the orient.

It is not just matter of him thinking that European civilization is superior. He was on a cultural mission to ‘civilize’ India by bringing up a class of natives which reflect his views. He also said, “we must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect”.

The problem with Macaulay’s views is obvious. It is worth commenting if they hold any water. It is true that Renaissance, Enlightenment, and Scientific Revolutions are great leaps in humanity’s efforts to unravel the natural world and establish governable societies but is it any measure to downgrade all the spiritual progress made in the orient? The East, specifically India, have been a center of learning for those interested in the ultimate nature of the divine. The whole Vedic tradition is second to none in its efforts to comprehend man’s relation to the universe as a whole, an area where European thought has lagged far behind despite scientific and cultural revolutions. The Indian and Arabic traditions boast of a rich contribution to areas of linguistics, astronomy, mathematics, and political philosophy. Add to that the invaluable service done by the orient in preserving Greek and Roman thought through translations and later through transmission to the Western world and you get a picture of the Eastern civilization without which the great Renaissance, Enlightenment, and Scientific Revolution would not have taken place.

The truth is that Eastern and Western intellectual traditions are built on different epistemological paradigms. Any effort to use one to denigrate the other is bound to be false and misleading. Holding Macaulay’s views in today’s “civilized world’ is deeply abhorring. But those were good old times when orientalist view of the world was the norm.

Has Macaulay been successful in cultivating a middle man that acts as interpreter between the British masters and the colonized masses? It may appear yes on the surface. However it is worth noting that the same middle man, i.e. the English educated Indians, acted as freedom fighters for the masses and helped end the British regime.

What happened after the Partition further dented Macaulay’s legacy. We may turn towards Pakistan at this stage. If we put aside, for a moment, the upper class schooling, the education in Pakistan has been largely Pakistanized. Through subjects such a Pakistan studies, Islamic studies, and introduction of elements of Islamic education in all areas including that of science, Macaulay’s dream has been largely shattered. However, the issue of English as a medium of instruction still begs the question. Does it not imply that Macaulay still lives and perhaps thrives in the land of the pure despite all cosmetic surgeries? To what extent does a medium of instruction become the message itself requires separate treatment. Here it would suffice to say that it does inculcate a sense of inferiority in those going through education in a foreign language. Which brings us to signify the education in one’s mother tongue or at least in the second easily comprehensible language. The main point of criticism that remains is the education delivered to the ruling class which is not just in English but is also devoid of all the spice used to make our children devout Pakistanis.

So one may concur that at least in one respect Macaulay’s legacy still lives on. And that is in the form of private schooling aimed at the children of the ruling elite. Now perhaps one immediately comes up with the idea of a National Curriculum of Pakistan where such class differences are meant to be abridged through a unified system of education. But this is not a sweet pill. As critics have been reminding us that any attempt to resort to a single curriculum is prone to merely downgrading the good private schooling in Pakistan without necessarily elevating the rotting public school sector. Perhaps the solution lies in upgrading the public schooling first; to introduce education in mother tongue, to modernize the public schooling, and to rid of the indoctrination done in the name of the religion.

Rab is a graduate of law and philosophy. Formerly an activist, he is currently working as an independent researcher