19% of the sanctioned seats for teachers lying vacant in Punjab: chilling revelations under the Right to Information Act

In a recent public address, Punjab Education Minister Murad Raas applauded the Insaaf Afternoon School initiative which involves upgradation of existing primary school infrastructure to run as elementary classes during afternoon to cater to students who otherwise feel compelled to drop out due to logistical and cultural barriers. In a matter of six months, as claimed by the minister, 7,000 of such schools have been converted to enable approximately a 100,000 girl-students to return to schools in just a matter of four months.

“If we had proceeded as per previous government’s plans, it would have cost us around Rs.290 billion and another 3-4 years to build elementary girls schools across the province. In comparison, we managed to cater our out of school children in a mere Rs. 5 billion in a very short time.”

While adding more more on this, he said that in coming phases the plan will further expand to turn these into evening schools to cater Higher Secondary classes for girls.

It is a great step indeed, especially when it comes to its promised cost-efficiency which is enabling girls to finally continue with elementary school and open up to the potential for higher education within their proximity. However, with this great claim of success comes an even greater question which has been puzzling economists and policy makers for long; who will be teaching when the province-wise teacher shortfall currently stands at a whopping 19% against the sanctioned seats?

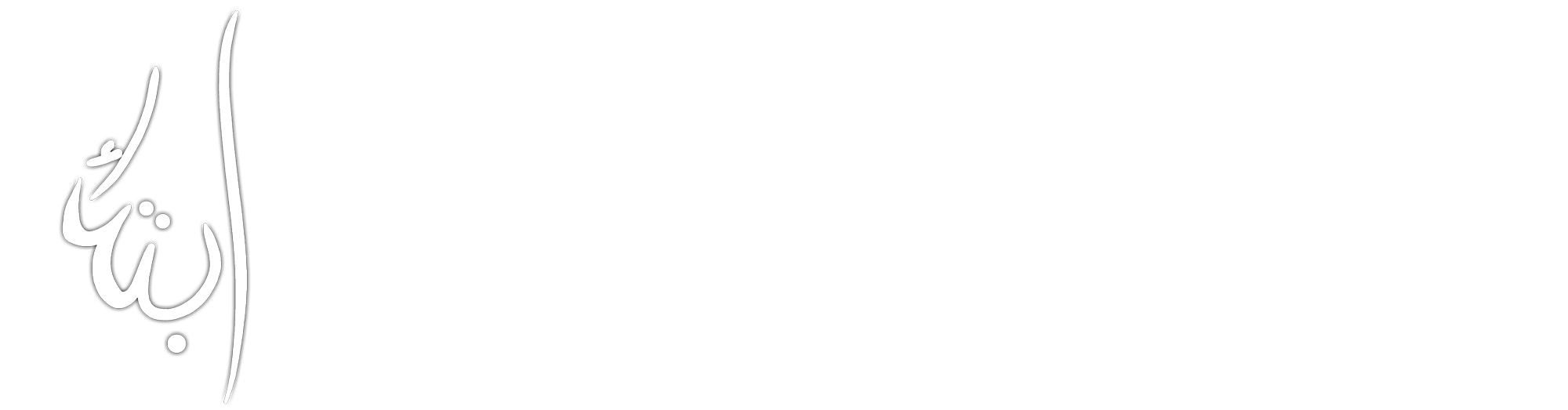

Status of Information Disclosed under Right to Information Act

The concern is further elevated by a recent revelation of 81,466 vacant seats against 433,134 sanctioned posts under the provisions of Punjab Transparency and Information Act, 2013 invoked by Mukhtar Ali, CEO CPDI and a staunch advocate for transparency and public accountability. While speaking to IFE, Mukhtar Ali mentioned about the resistance from district education authorities in providing the data, and it was acquired only after the intervention of Chief Information Commissioner.

“The numbers that we see are very shocking and indicate towards multiple factors leading to the teacher crisis in the province. A major blame should be placed on keeping education a low prioritized area, and it’s sad to see no serious efforts are made to address our most vital issues.”

He further expressed his disappointment over the difficulty his team faced in acquiring information from each district’s education authority,

“It is sad to witness that our basic right to information is gravely undermined here by the authorities. Weak understanding of the law and its implementation here are starkly noticeable.”

He further pointed towards more serious disparities observable within the districts, and stressed on the need to probe more into the causes of this.

“An indication is there of a lack of rationalized policy on recruitments. There may be examples of teacher surplus in one place and the shortage in another, which further must be be looked into. As has been observed in the past, stalling of recruitment processes during a government’s tenure and then filling the vacancies right before elections for political mileage have been the most damaging practice of our politicians, and it has caused serious losses to our students and schools.”

The Catastrophic Numbers

A comparison of the ratios of vacant seats among all 36 districts reveals Sialkot having the lowest share at 13% whereas Jhelum, shockingly, has the highest at 39% (out of 4,034 seats, 1,591 are laying vacant). About 55% of the districts (i.e., 20 out of 36 districts) have over 20% vacant seats, while for the rest of the districts, the vacant seats lie at 15% or above (with the exceptions of Jhang and Sialkot both of which have over at 14% of the vacant seats).

To provide an idea to our readers on the extent of disparities within a district, we at IFE made an analysis of select districts based on the information provided by district education authorities. Starting with Jhelum because the information reveals the highest number of vacant seats against sanctioned posts in Punjab province.

Situation in Jhelum

If the numbers mentioned in stamped copies provided by the Education Officer in Jhelum are to be believed, then the district is embroiled with serious teacher shortfall for 39,553 enrolled primary school children at their foundational level of learning in the district (enrolment statistics taken from School Census Report, 2020/21). The information received on teachers as per their pay-grade level has revealed 1,098 sanctioned posts against which 1030 seats are empty. That makes a 94% of teacher shortfall for primary schools alone. Other indicators point towards an 80% subject specialist shortfall for 182 secondary and 12 higher secondary schools in the district. We must bear in mind that secondary and higher secondary are important years to prepare students for advanced classes so they can transition into college or universities. How can that be accomplished when there are no teachers available to guide them through?

Situation in Faisalabad

The school census 2020/2021, as posted on the Student Information System shows the highest number of enrolled students (standing at 820,423) in the district’s public schools, however, the information disclosed under RTI Act is quite worrisome over teacher availability to cater this population. For the 221,418 students enrolled in 1,178 primary schools, about 15% of the sanctioned teacher posts lying vacant. Quality of education in secondary and higher secondary schools is severely affected by the subject specialist shortfall of 52.3%. In terms of administration, about 40% of the posts for Principal (sanctioned posts for grade 19 and 20 are 161) are empty for 12,699 schools. For the headmasters, 59.12% of seats for grade 17 and 18 (255+134) are also lying vacant in the district. Overall, based on the information provided by district education authority, the teacher shortage in the district stands at 18.06%, despite having the highest number of enrolled students.

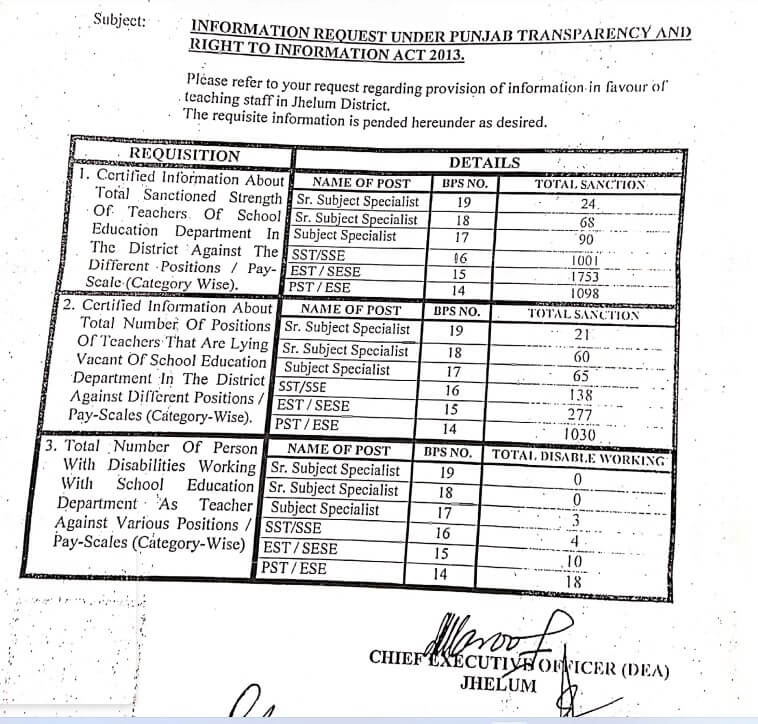

Trends in Teacher Strength as per Government’s School Census

Based on the government’s own published data, we observe a steady decline in the teacher strength trend since 2018. We also see a stark decline in teacher strength for primary and elementary teachers, and nominal positive trends in recruitment in secondary and higher secondary level schools.

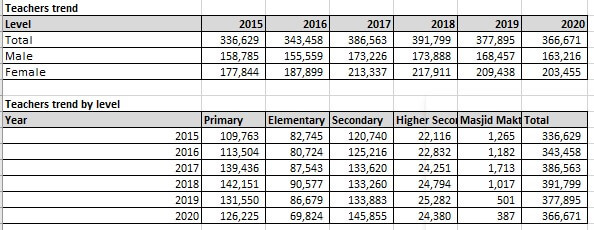

Trends in Primary Teacher Strength

Since 2015, the number of teachers rose from 109,763 to 126,225 by 2020. The highest number of recruitments were observed between 2016 to 2018, with an increase by 29.5% in teacher recruitments for primary, which rose to 142,151. However, the upward trend was not maintained, and a declining trend is strikingly noticeable with a drop of numbers by 11% between 2018 and 2020. (drop by 10,601 teachers in 2019, and by 5,325 in 2019)

Trend in Elementary Teacher Strength

The most worrying observation is the drop in teacher strength by 19.4% in a single year in 2020. In 2015, the strength was recorded at 82,745 which rose by 9% in 2018. The highest number of recruitments were observed in 2017, however, between 2018-2020, the drop in the strength is estimated at 23%.

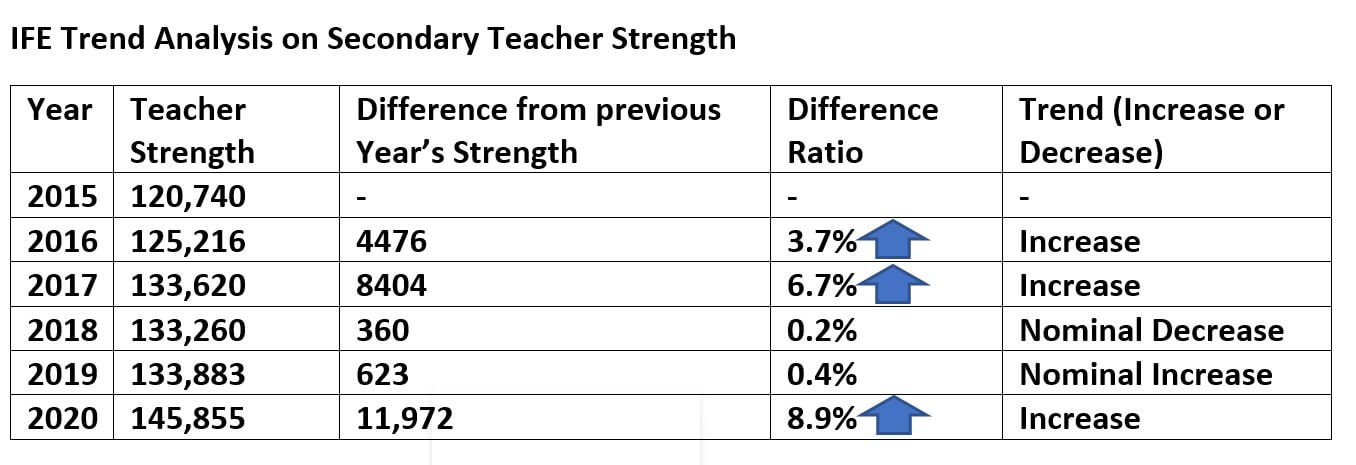

Trend in Secondary Teacher Strength

During 2015-2020, there are two instances where rapid increase is noticed, one in 2017 and the other in 2020. Besides the nominal changes in 2017 and 2018, a secondary level teacher recruitment sees a positive trend, unlike recruitments in primary and elementary schools. Since 2015, there has been an increase by 21% in teacher strength in the province.

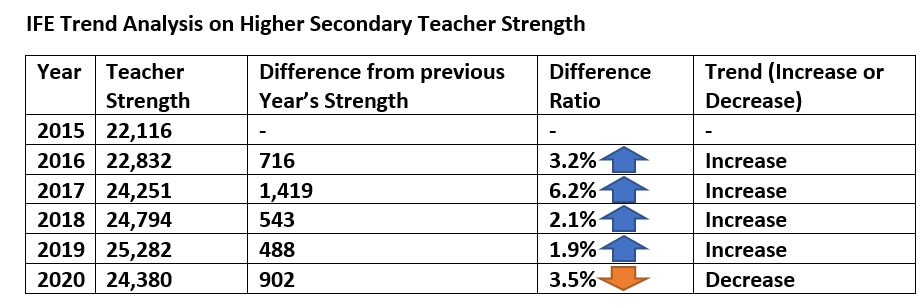

Trends in Higher Secondary teacher strength

Between 2015 -2019, there has been an increase in teacher strength by 14.31%, with a sharp rise in recruitment in the single year of 2017 by 6.2%. However, 2020 alone saw a slight decrease in strength by 3%, bringing the teacher strength to 24,380 in 2020.

Teacher Shortfall and the Issue of Rationalization

The online portal shows over 5,000 teachers expected to retire from service in 2022 and another 6,300 teachers will retire in 2023. That makes about another 11,300 teachers vacating their seats very soon. Add to the list the “erratic postings” of the teachers, which are 4,421 in total, which means they will be transferred to other districts as they leave behind a void in the schools they’re currently posted at. With almost nil new recruitments between 2018-2020, and the increasing trend in teacher shortfall, where are we really headed?

To understand the term “erratic postings”, and the factors contributing to teacher shortfall, we talked to Muhammad Imran, President Punjab Teachers Union, Rawalpindi Division. He said:

“The rationalization policy that the Punjab government had recently devised was completely cut off from our local realities. We have issues of over staffing in some schools, while others remain seriously understaffed. The result? a very poor Students per Teacher Ratio (STR). We’ve been trying to explain to our policy makers that you cannot keep the same yardstick for rationalization across all regions of Punjab. For example, the topography and social environments are different in upper Punjab than the conditions we see in the South. And a complete aloofness on the regional sensitivity by the bureaucracy is disappointing as they decide on teacher transfers.”

While criticizing the much-publicized e-transfer policy introduced by Punjab Government, he added:

“It’s another backdoor channel devised for favouritism. What we fail to see are the blatant violation of the rules, whereby the transfer decision has been handed over to the Punjab Information Technology Board, instead of the local CEO’s who carries the actual authority to decide on the matter. Furthermore, the criteria set for it is not clear. They have not defined “hardship” and “extreme hardship”, and have kept the terms very vague. We have a genuine problem of local teachers, especially women, to transfer to other districts. The local teachers will serve better within their districts, and this is where the government needs to rationalize, as per our ground realities.”

The Teacher Protests

Imran further expressed discontent over the populist announcements made by leaders without considering what’s actually happening on ground. On the opening of Insaf Afternoon Schools, he expressed his skepticism by pointing towards an already running Basic Community School initiative of the previous governments, which is working under the same model with overworked and underpaid teachers.

Another major suffering is that of the salaries and the failure of the government to notify the service and pay-protection policy of the now regularized teachers. Thousands of teachers are again protesting in front of Punjab Secretariat in Lahore over the neglect of this. The procedural delays, the ambiguity in the previous recruitment policies, and a lack of social protection mechanism for the teachers have been resulting in their pay reductions. The court has recently given its verdict in favor of teachers’ petition for service and salary protection; however, no notification has been issued by the government yet, much to the dismay to the teacher community.

Muhammad Ramzan, the Secretary General of Punjab Teacher Association based in Faisalabad, highlighted more on the multifaceted grievances of the teachers during his conversation with IFE.

“Since 2018, the teacher recruitment process in the province has been stalled. We have a policy of 50% recruitment for new teachers and 50% for those who are in-service. However, promotions have been stalled whereas many teachers are waiting for it for decades. Unless they get promoted, room for fresh recruits can not created. It’s highly unfair and extremely demotivating for the teachers who are denied job protection and basic respect by the bureaucrats.”

On the issue of salaries, he said besides abysmally low basic pay, the rent and conveyance allowances haven’t been revised since 2008.

“This is how they prioritize education. With such discouraging conditions for teachers, how do you expect them to generate and attract new recruits at a time of such education crisis in Punjab? Those already in service are suffering because they don’t really know how to make their ends meet and survive rising inflation. They will eventually opt for other opportunities and nobody will be left to teach our students, who too will feel compelled to drop out. This is a disaster.”

Where is the money against 19% empty sanctioned posts going to in Punjab?

This IFE researcher attempted to reach the concerned officers for their comment, but met with failure to make a relevant contact. The questions we had intended to ask was what steps are the School Education Department taking to address the teacher crisis in the province. Furthermore, the analysis based on the information acquired under RTI compels one to ask from the authorities as to where the unutilized salaries against empty posts are being directed to? It is an important question to ask while keeping in mind of the claim of over 80 to 90% of the education budget in the province getting consumed by non-development expenditures (teacher salaries) of education—a claim that now needs a more convincing justification as there has been a persistent decrease in the teacher strength since 2018. Even if Punjab’s Education Minister, Murad Raas is claiming cost-efficiency through Insaf Afternoon Schools, how will he be able to address the structural fault that lies at the heart of not matching up his ministry’s new initiatives with the teachers’ existing capacities?

What future is in store for education in the province, one can only shudder at the thought.

Authored by Zeeba T. Hashmi. For a complete district-wise analysis on teacher shortages , you may email her at the following address: zeeba.hashmi@gmail.com